During the period 1894–1971, the Criminal Code of Finland (chapter 20, section 12, subsection 1) forbade sexual acts between members of the same sex. Although penalties were required by law, few offenders were convicted during the early decades of the ban. From the 1930s onward, the number of sentences for homosexual acts gradually increased, peaking in the 1950s. A total of 1,074 people were convicted, 51 of whom were women. Cases involving women rarely reached courts, and those informing the police about female offendersoften had other motives for doing so than concern about the homosexual acts themselves.

The law against homosexual acts was not actively enforced by the police. In Tampere in the 1950s and 1960s, the police felt no need to intervene against “that kind of men” but considered it sufficient to know who they were. The police had, of course, limited resources at their disposal to spend on preventing homosexual acts.

The Vagrancy Act entered into force in 1936. The purpose of the law was to control the sexual morality of citizens. Enforcing the law was the duty of the police and vice committees, and practical monitoring was performed by vice squads. The photograph was taken at an education day for detectives and vice officers in 1958.

Image: M. Laitinen, Vapriikki Museum Centre, Vapriikki Image Archive.

Similarly, the ban on encouraging homosexual acts neither led to penalties nor active police surveillance. Although legislation had failed to prevent homosexual relations, homosexuals had to take into account that they were breaking the law if one of the parties in the relationship was below the age of consent. A homosexual man who entered a relationship with a younger man in the late 1980s reflects on his relationship:

My former boyfriend was 17 years old, I was 25. We were together for several years, and I have kept in touch with his parents even after that. This bears witness to their tolerance concerning both our homosexuality and our age difference. Our relationship was supported by the family even though it was illegal.

Members of sexual minorities often felt that the criminalisation of their sexual activities reduced their quality of life and human dignity. One’s sexual orientation could lead to crises including severed social ties and fear of losing one’s reputation or job. In addition, the illegality of homosexual acts created an aura of lawlessness and even danger around one’s lifestyle. Secrecy and a culture of being quiet about one’s sexual orientation became part of everyday life.

Sexual minorities often distrusted the police, both due to the criminalisation of homosexuality and the unfavourable attitude of many police officers toward sexual minorities. The police did not always intervene against violence and other crimes directed against homosexuals. This kind of “none of our business” thinking contributed to self-discrimination and shame among homosexuals, making them less inclined to report crimes or seek help when subjected to them. The decriminalisation of homosexual acts in 1971 did not immediately reduce prejudice against homosexuals.

The criminalisation of homosexual acts forced homosexuals to hide their identity. The desire to meet others in the same situation created alternative ways of signalling that one was part of a sexual minority. An earring, a long nail, a ring on one’s little finger or a scarf in one’s back pocket were well-known signals that were used in many countries. Homosexual culture sometimes also included cross-dressing and the use of nicknames that did not reveal one’s gender.

Image: E. Laakso. Finnish Heritage Agency, Historical image collection.

Hate crimes and hate speech

According to Finnish law, hate crimes are crimes motivated by prejudice or malice toward a person or group on the basis of, for example, nationality, ethnicity, religion or sexual orientation.

Crimes against homosexuals include violence and hate speech. In 2019, a total of 899 crimes possibly motivated by hate were registered, 51 of which on the basis of sexual orientation and 21 on the basis of gender identity or transsexualism. A clear statistical trend towards an increasing amount of hate crimes has been seen in recent years, and the vast majority of victims of violent crime are male.

It has been noted that hate crimes are sometimes not reported to the police since victims do not trust that the matter will be taken seriously. It would, however, be important to tell the police the background of the crime in sufficient detail so as to enable them to investigate it as a hate crime.

Linnea West, Senior Detective Constable, Chairwoman of Rainbow Police of Finland

Hate speech is often motivated by religious views of homosexuality as a sin and sometimes an illness. The police have limited resources to spend on rooting out hate speech. There is a lack of precedents concerning hate speech, and it is difficult for the police to know what kind of speech must be tolerated and what kind of rhetoric fulfils the criteria of illegal hate speech. In the age of social media, hate speech has grown further as a phenomenon and can be quickly spread to a large audience online.

In 2016, a counterdemonstration was organised in opposition to a demonstration against refugee reception centres in Tampere. The pink sign in the centre of the image reads ”Stop the hate speech”.

Image: Anne Lahtinen, Finnish Labour Museum Werstas image collection.

Violence

Little research has been conducted on violence against members of sexual minorities or violence committed by them. Studying this topic is difficult due to many crimes not being reported and due to the omission of details pertaining to sexual orientation during the preliminary investigation. For example, sexual orientation is not always brought up as a motive for the violence, and the sexual orientation of the perpetrator may not be registered.

The criminalisation of homosexuality and enforcement of this law left a deep impression in the minds of many. Fear of penalties compelled some homosexuals to hide their sexual identity.

Image: Police museum.

The threat of violence is present in the lives of many members of sexual and gender minorities. For example, children and adolescents living in otherwise heterosexual families may be subjected to violence due to their identification with sexual or gender minorities. According to a survey on wellbeing among school pupils conducted in 2019 by the Finnish Institute of Health and Welfare, rainbow adolescents were more likely than their peers to be subjected to not only bullying in the form of name-calling and physical threats, but also to psychological and physical abuse committed by parents or other guardians at home. Child protection authorities and the police often have to intervene and assign the child or adolescent to foster parents who are tolerant and supportive of sexual and gender minorities.

Listen to Mikko Ala-Kapee’s account of violence directed against rainbow children.

Some members of sexual and gender minorities are subjected to violence because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. This homophobic, lesbophobic, biphobic and transphobic violence is based on a heteronormative premise that justifies hitting those who deviate from the norm. This attitude is characteristic of the sexualised and genderised bullying and name-calling prevalent in schools and youth culture. Failure to intervene against bullying, harassment and name-calling among children and adolescents permits some young people to act violently against those they do not consider as valuable as themselves. Violence against members of sexual and gender minorities and those suspected of belonging to these groups is motivated by a desire to mark the difference between true and false gender.

Lehtonen, Jukka 2007. Seksuaali- ja sukupuolivähemmistöt, väkivalta ja poliisin toimet (Sexual and genderminorities, violence and policeefforts.) Minna Centre for Gender Equality Information, Helsinki.

When violence occurs between adults in a relationship, a typical pattern is that the violence increases gradually. What begins as verbal abuse may turn into physical abuse. Those involved are often unwilling to talk about the violence, one of the reasons being that domestic violence is nowadays, as opposed to previously, investigated by the police and subject to prosecution even if the injured party does not request it. The fear of detection thus prevents many victims of domestic violence from seeking help. Another reason for secrecy may be that the person is in a marginalised position for multiple reasons, being a member of a sexual or gender minority while also being a victim or perpetrator of domestic violence.

Collaboration between the police and the regional branches of Seta plays a key role in the investigation of crimes directed against sexual minorities. The presence of sexual and gender minorities within the police force increases the competence of the police and public confidence in their ability to investigate crimes. The photograph shows a shoulder tag carried by London police officers.

Image: Linnea West.

The risk of being subjected to violence is particularly high among members of sexual and gender minorities who simultaneously belong to another kind of minority, such as people with disabilities, immigrants, non-Finnish-speakers or transsexuals. According to an inquiry by Transgender Europe, 350 transsexuals, 343 of whom were trans women, were subjected to violence in 2020.

Chemsex events, which are centred on sexual intercourse between males combined with use of illicit drugs, have so far been rare in Finland but occur frequently in major cities including London and Berlin. Chemsex events are illegal due to the use of illicit drugs, and risks associated with Chemsex include that of being raped or subjected to other kinds of violence. While under the influence of drugs, it is more difficult to uphold personal boundaries and treat others in a respectful manner.

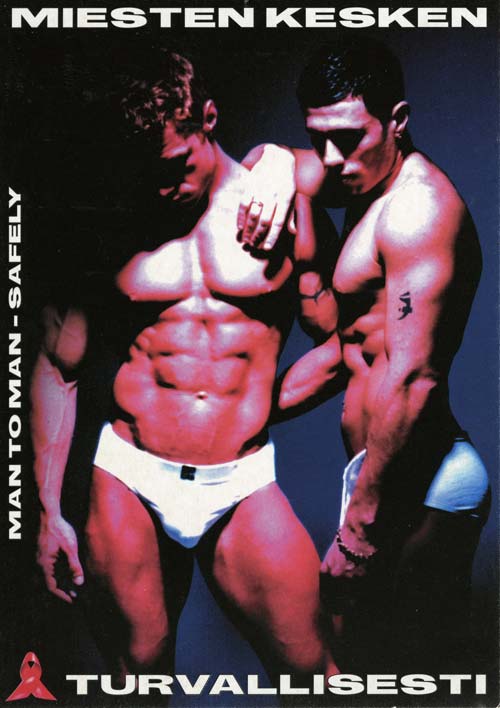

Image: Hans Fahrmeyer, card from the AIDS Support Centre of Finland, Finnish Labour Museum Werstas Image Collection.

Discrimination

A ban on discrimination was included in the updated Criminal Code of 1995. Employment discrimination directed against employees and job applicants based on their sexual orientation is prohibited.

The law did not prevent discrimination from taking place at work or outside of work. The most publicised case of discrimination in employment decisions occurred in 2008, when a journalist who had been hired as editor-in-chief of the newspaper Lapin Kansa suddenly found her employment contract terminated already before she had begun working. The employer, newspaper company Alma Media, justified this decision by stating that there was a lack of trust since she had not, during her employment interview, mentioned that she lived in a same-sex relationship and that her partner was politically active. The journalist, in turn, claimed that her employment contract had been terminated because of her registered partnership with another woman. The Court of Appeals found the CEO of Alma Media guilty of employment discrimination based on sexual orientation, and the Supreme Court did not grant a leave to appeal.

Speech can also contain elements of discrimination. In a May 2015 episode of Nelonen Media’s reality TV series Poliisit – kotihälytys (The Police – Home Disturbance), police officers discussed a case involving violence between three men. The police officers used the word ”homppeli” (“fag”) about the men involved. Seta declared this term to be discriminatory against sexual minorities and thus highly detrimental with regard to its consequences. The use of such words reduces public trust in the police and may discourage victims of crime to seek the help of the police when crimes occur.

News reports on violence and other crimes

News reporting on crimes plays a major role in society. Reports on discrimination, drug abuse and violence involving members of sexual and gender minorities as victims or perpetrators contribute to the public image of these crimes. Most news reports are socially relevant, moderate and ethical, but a minority of them are created for entertainment purposes, appealing to emotions rather than focusing on the facts of the crime.

The police have access to a great amount of information on crimes, and informing the public about them is among the duties of the police. When informing the public, however, the police must carefully consider what kind of information and how much of it can be communicated without interfering with the investigation or revealing more than is legal.

In June 2020, the country’s first widely publicised case of homicide involving a trans woman as a victim occurred. The first police report mentioned a stabbing that had resulted from a quarrel between men. Those who knew the victim, however, noted that the victim had, for several years, lived openly as a woman, including on social media. What had been described as a quarrel between men had thus actually been the killing of a trans woman, a member of a gender minority. In their initial report, the police had relied on a public registry that listed the victim as a man.

The current Finnish legislation on transsexualism requires candidates for sex reassignment to undergo a medical and psychiatric evaluation. This requirement is sometimes felt to constitute an obstacle to the formal recognition of a transsexual’s gender. Following the aforementioned case of homicide, the police have stressed the importance of taking into account the sexual and gender identity of both victims and perpetrators in order to correctly identify motives that may classify the acts as hate crimes.

News reports on crimes against members of sexual and gender minorities often emphasise the connection between the victim’s lifestyle and the violence or other crime at hand. This kind of reporting may uphold and add to negative stereotypes about sexual and gender minorities. This photograph from the 1930s shows a crime scene where a man had hit another man to death. It turned out that the act of violence had been provoked by sexual advances.

Image: Police Museum.