The criminalisation of the homosexuality began during the Middle Ages, when Finland was part of the Kingdom of Sweden. In the late 13th century, the Catholic Church decided that acts of homosexuality were to be punished. This decision was based on the biblical account of the Sodomites, men who wanted to have sexual intercourse with other men. The sexual interest in members of one’s own sex characteristic of the Sodomites was considered a sin punishable by death according to Leviticus.

Secular law began prohibiting acts of homosexuality only from 1608 onward. The law was formulated in greater detail at the end of the century. Sodomic sins, as homosexuality was referred to in legal tradition, were grouped with bestiality.

According to the new Criminal Code that entered into force in 1894, unchaste acts between members of the same sex, i.e. homosexual relations, were subject to penalties. Unchaste behaviour included not only sexual intercourse, but everything that violated sexual morality, such as inappropriate touching.

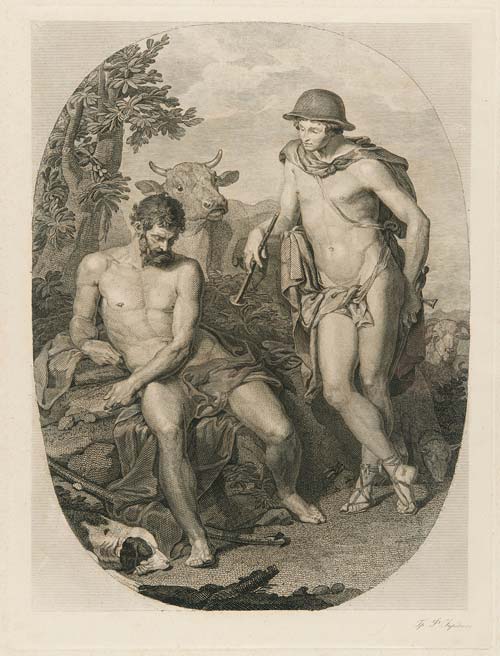

Image: Artist Fyodor Ivanovich Iordan. Finnish Heritage Agency, Historical image collection, Enckell collection.

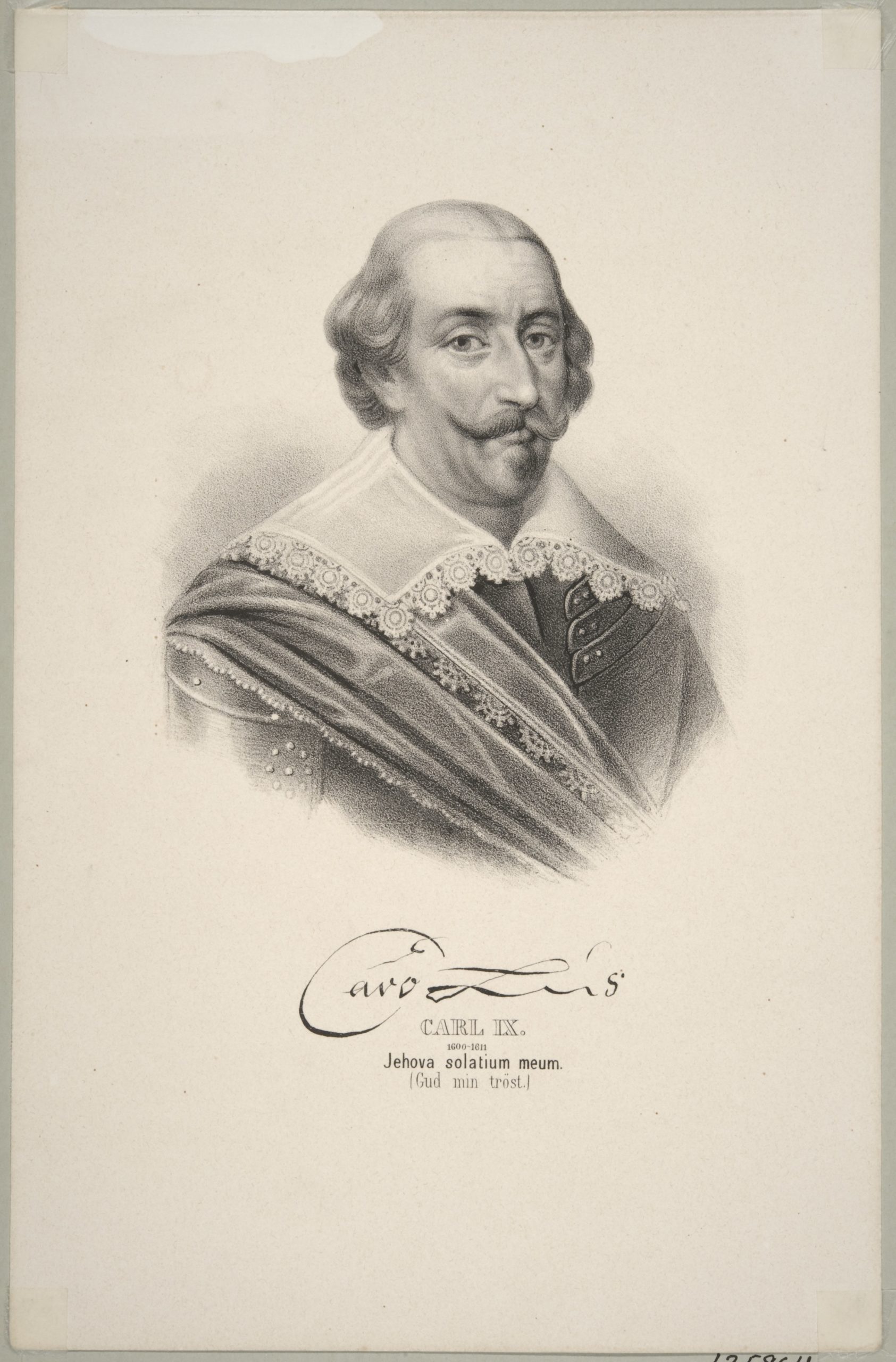

King Charles IX added a prohibition of homosexuality to the law of the kingdom. During the 17th century, those who committed acts of homosexuality were punished publicly as a warning to others.

Image: Finnish Heritage Agency, Historical image collection.

Laws regulating homosexuality were developed further in the 19th century after Finland had become part of the Russian Empire. Following extensive preparations by statesmen, the Criminal Code of the Grand Duchy of Finland entered into force in 1894. The law forbade unchaste acts both between men and between women.

Finnish law was strict in the sense that homosexual acts between women were illegal, which was not the case in many other European countries at the time. The law also forbade poses that included sexual signalling or were considered arousing in other ways. Sexual intercourse for the purpose of procreation remained the standard of natural sexuality. Sexual relations outside of marriage were subject to penalties according to the Criminal Code.

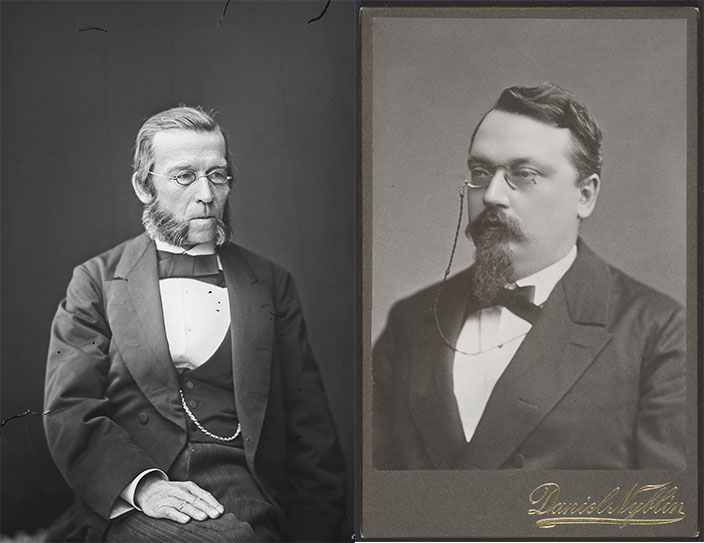

The new Criminal Code was prepared by two committees, the first led by Karl Gustaf Ehrström and the second by Jakob Oskar Forsman. The text of the proposed Criminal Codewas completed in 1884. The text defined homosexuality and bestiality as separate subcategories of unnatural violations against chastity.

Images: Daniel Nyblin. Finnish Heritage Agency, Historical image collection, Atelier Nyblin collection.

The Criminal Code underwent further revisions during subsequent decades. The Vagrancy Act of 1936 included mention of homosexual acts. Unchaste behaviour and abnormal sexual drive, including sexual relations with a person of the same sex, was condemned. The negative attitude toward homosexuality was further strengthened in 1952, when homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder.

Changes in society were, however, of greater significance than legislative changes in terms of how homosexuality was regarded. Urbanisation in particular changed the way in which the local community exercised control over homosexuals. In the 1950s, many urban dwellers considered the topic indecent, and the establishment in particular avoided bringing it up. In the urban setting, the responsibility for monitoring homosexuals fell on the police, who, however, intervened against homosexual acts mostly based on tips from the public and often simply ignored this category of offences.

In the 1880s, issues pertaining to sexual morality and chastity were discussed among the intelligentsia. Authors Minna Canth and Juhani Aho commented on prevailing sexual morality in their works and described these aspects of human life in a strong, realistic way. Minna Canth reflected on the issue of female emancipation: “It is assumed that chastity would disappear from the world as the woman gained more freedom. It is feared that her views on chastity would become as confused and lax as those of men if the external forces that have so far kept her within the confines of chastity suddenly were to be abolished. Quite on the contrary! Let her be enlightened while she gains her freedom…” (Valvoja 4/1884).

Image: Finnish Heritage Agency, Historical image collection.

Listen to a contemporary’s account of attitudes toward homosexuality at the time.

In my hometown in Kainuu in the 1950s, the atmosphere was more open and tolerant than in Helsinki. Gays were called man-lovers, lesbians were called man-haters. Both had always existed in the area, and they had been allowed to live peacefully as part of the community.

Contemporary

Listen to Jorma Hentilä’s account of gathering places for homosexuals.

Mounted police officers often patrolled the stone wall by Laakso Hospital and the rocks of Mäntymäki, places where homosexuals were known to meet each other. At one point I climbed up on a rock while fleeing from a police horse. The police issued fines and signalled to homosexuals to come closer to the police cars. There were also bands of robbers in these areas, and they would occasionally commit violence against homosexuals.

Contemporary

The number of people penalised for homosexual acts gradually increased from the 1930s onward. Initially, 6–30 offenders were sentenced to penalties annually, and this number peaked at 40–80 in the 1950s. The vast majority of offenders were male. In newspapers, concerned citizens expressed their dislike for homosexual acts in public parks and restrooms, demanding the police to intervene.

[The public restroom of the railway station] has become a gathering place for homosexualists, and the most disgusting of acts are committed here. The worst part of it is that the homosexuals do not allow others to use the restroom in peace. Are the authorities unaware of what is happening here?

Helsingin Sanomat 4.1.1966

On 10.8.1966, Ilta-Sanomat published an article on a den of homosexuals that had now been uncovered. A homosexual man had offered to rent out part of his home, and a journalist from Helsingin Sanomat had assumed the role of a person interested in renting it. The landlord had mistaken the journalist for a homosexual and thus dared to speak openly about his homosexual lifestyle. This had given the journalist plenty of material for his article. After the article was published, the homosexual landlord was sentenced to a penalty.

Jorma Hentilä, former Chairman of Seta

Extensive changes to sections of the Criminal Code dealing with sex crimes were prepared in the 1960s. The proposed changes were collectively known as the sex package since it also involved legislation on abortion, sterilisation and castration. Finland still lagged behind other Nordic countries regarding equality and minority rights, and the need for legislative changes regarding homosexuality was imminent.