The police collaborate with Seta, an association promoting the human rights and equal treatment of sexual and gender minorities. This collaboration can be seen by the wider public during the annual Pride festival, where the police are present to guarantee the safety of the participants. The event has been organised since 1975. Originally, it was known as the Liberation Day, but since 2000 it is known as Pride.

The police have the duty to guarantee the right to peaceful assembly. This includes protecting participants of the Pride festival against those who want to disrupt the event. Since the 1980s, the police have made plans for securing safety at the Liberation Day and Pride events and assessed possible threats against them. In dialogue with Seta, the police have determined how many officers are needed at the event and how the route of the parade can be secured to allow marchers to proceed as planned.It has always been necessary to analyse threats and make sure that security can be upheld, especially if threats against the event have been made in advance.

Pride marches are organised all over the world. The purpose of Pride is to support the right of sexual and gender minorities to express their identity and take pride in their sexual orientation.

Image: Pridemarch with mounted police. Melissa Hanhirova. Finnish Heritage Agency, Historical image collection, Melissa Hanhirova – Helsinki Pride collection.

A major attack on the Pride parade took place in Helsinki in 2010. Three men attacked participants with gas bombs, teargas and pepper spray. A total of 88 people were injured. Soon afterwards, someone smashed windows at Seta’s headquarters in Helsinki. Another Pride event held in Oulu was also targeted by violent opponents.

Image: Attack on Helsinki Pride in 2010, Yle.

Pirkanmaa Seta and the police collaborate to secure equal and non-discriminatory treatment for crime victims belonging to sexual and gender minorities. Pirkanmaa Seta may, for example, help crime victims come to the police for help and report the crime committed. The association can facilitate this by contacting the police in advance and inform them about the victim’s background, including by which name the person prefersto be addressed. A consultant from Seta may also accompany the victim or perpetrator to make sure that the encounter with the police is non-discriminatory.

Pirkanmaa Seta educates police on the practical application of the Equality and Non-Discrimination Acts. The focus of the education is on preventive work and awareness of attitudes.

Seta, an association for promoting the rights of sexual and gender minorities

Seta ry, a Finnish human rights and social issues NGO, was established in 1974. Seta’s mission is to promote social equality regardless of sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression. Seta ry is a national umbrella organisation with 27 member associations across the country.

All people are entitled to the realisation of human rights in all areas of life. Sexual orientation or identity should not, and neither should other sides of one’s personality, limit a crime victim’s access to help, a job applicant’s opportunities to gain employment, or a refugee’s chances of being granted asylum. Seta participates in domestic and international political discourse on such current matters pertaining to human rights.

The regional Seta association of Pirkanmaa is a local political influencer and offers its members social support, peer support, expertise, recreation and cultural services. Pirkanmaa Seta administers the nationwide support and counselling service Sinuiksi, the purpose of whichis to increase knowledge about matters pertaining to sexual orientation and gender identity.

Asylum seekers and the authorities

The prolonged conflicts and humanitarian crises in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Africa as well as various political, economic and social reasons have motivated many to seek refuge in Europe. The refugee crisis that swept across Europe in 2015 brought more than 32 000 asylum seekers to Finland. During the autumn, a centre for the initial reception of asylum seekers was established in Tornio by the Swedish border as a joint effort by several authorities. The police received and registered asylum seekers at the centre and monitored several protests organised by Finns who demanded that the government “close the border”.

Belonging to a sexual or gender minority can be a reason for seeking asylum if the asylum seeker’s mental or physical well-being is threatened on the grounds of sexual orientation or gender identity. Persons from some cultures may, however, find it difficult to be frank about their sexual identity, perhaps due to having been judged by others previously. The situation may become particularly problematic for the asylum seeker if asylum is not granted.

Travelling from one country to the next is difficult and mentally exhausting for asylum seekers. Those belonging to sexual or gender minorities are in a particularly vulnerable position. Violence, threats and even rape may occur at refugee reception centres. Asylum seekers who lack permission to stay in the country may not dare to seek the help of the police when subjected to violence.

The Finnish Immigration Service and the reception centres collaborate with Seta, which educates their employees on sexual and gender minorities. Seta may also send a consultant to be present at encounters between police and asylum seekers.

Police registering recent arrivals at the Tornio centre for the initial reception of asylum seekers in 2015.

Image: Jukka-Pekka Toivonen, Police Museum.

The significance of the legislation on transsexualism

The current Finnish law on transsexualism entered into force in 2003. The Act on legal recognition of the gender of transsexuals regulates sex reassignment treatments and the correction of gender. Transsexualism is understood as a discrepancy between the gender assigned at birth and the person’s subsequent gender.

The law has received criticism for its requirement that persons seeking formal recognition of their gender must produce evidence of being infertile, not being married, having reached adult age and having undergone medical evaluation. In addition, the person must produce evidence of having adopted the gender role of the new sex. These requirements are not in harmony with international treaties, self-determination and children’s rights. The United Nations, the European Union, Amnesty and Seta have pointed out the contradictory nature of Finnish legislation in this regard, but so far no proposition to adapt the law to human rights has reached Parliament.

Seta ry and Trasekry, a nationwide association focusing on the rights of gender minorities, have, along with more than 70 other organisations, issued a statement on changing current legislation on transsexualism. According to their proposition, the law should be modified to allow individuals to formally register as belonging to the sex of their choice without having to obtain a certificate from a physician as evidence of belonging to the opposite sex. The proposition also considers the aspect of gender diversity, suggesting the addition of a third gender to the public registry and formal documents.

It would be important to make personal numbers independent of gender identity. The option “Other” should be added to identity cards to take into account those who do not identify as men or women. Current legislation on gender equity prohibits discrimination based on gender identity, but the old classification system based on so-called legal gender contradicts this principle.

Mikko Ala-Kapee, Executive Manager, Pirkanmaa Seta

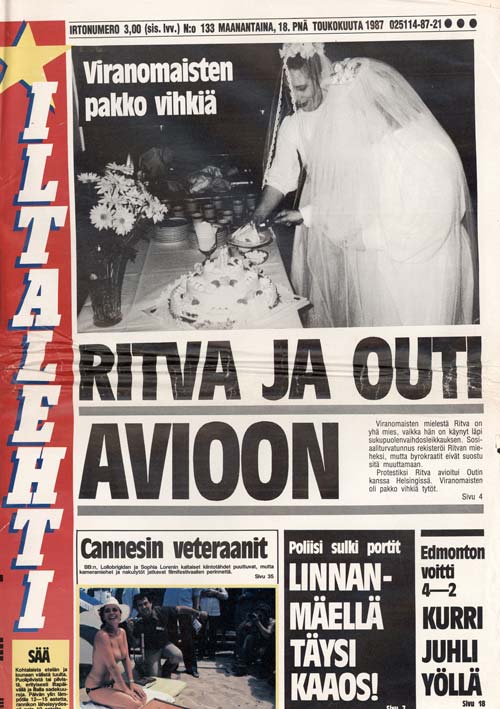

The discussion on changing personal numbers was ongoing in the 1980s, when Iltalehti published an article about two women, Ritva and Outi, getting married. In this particular case, same-sex marriage was legally possible since Ritva, who had previously undergone the formal sex reassignment process, had retained her male personal number.

Image: Ritva’s and Outi’s wedding. Collection of Finnish Labour Museum Werstas.

Media and popular culture

The current multifaceted image of homosexuality in media has evolved over a long period of time. Previously, depictions of sexual minorities in popular culture were based on the so-called tragic view, according to which homosexuals were never happy and typically died as a result of violence or AIDS. Exaggerated stereotypes were also common, featuring homosexuals as humorous minor characters. Over time, more carefully developed characters belonging to sexual and gender minorities emerged as equals to the heterosexual main characters of TV shows and films.

Until the 1960s and 1970s, books and programmes about sexual minorities were censored in Finland. Publishers removed references to homosexuality from literature, and media companies shelved TV programmes about the topic. The programme ”Oletko sinä…?” (”Are you …?”), written by Jarmo Salas and Rauno Vinermo in 1969, was among the programmes shelved for fear of violating the ban on encouraging homosexual acts. The programme was eventually broadcast by Yle in 1999.

Here you can watch Yle’s recent history series ”Arkistosta revittyä: Homot” (“From the Archives: Homosexuals”), which presents the history of sexual minorities and analyses the reasons why ”Oletko sinä…?”could not be broadcast in its own time. The series also discusses how the visibility of homosexuality in media has changed over time.

Watch the documentary ”Arkistosta revittyä: Homot” (in Finnish only).

In 1975, a few years after the decriminalisation of homosexual acts, Yle produced the documentary“Homoseksuaalisuus – eräs vähemmistö” (”Homosexuality – a minority”), which presented views for and against homosexuality among citizens. In the documentary, university scholars and healthcare professionals explained why a person might become a homosexual. According to the theory presented, the most important reasons stemmed from the childhood of the person, the family structure and the atmosphere within the family, often involving a troubled relationship with the father figure.

Watch the documentary ”Homosexuality – a minority” (in Finnish only).

The presence of sexual minorities in media and public discussion on them increased in the 1980s. This trend was turning sexual minorities into an everyday topic. Toward the late 1990s, sexual minorities were already taken for granted as part of society, and their visibility in media increased further. The language and terms used when referring to sexual minorities were also evolving, indicating that attitudes in society were changing:

Homosexuality was originally referred to as homophilia, where philia means love. This term as such focused on the love aspect of homosexuality. Similarly, the term homosexualist signified a person with a certain interest, as in philatelist. Later, for a long period of time people only talked about perverts and normals. Heterosexuality as a concept emerged only in the 1990s, before which heterosexuals had been referred to as normals. Many people, particularly among members of the majority, may react at this change, wondering why the old words are now invalid.

Jussi Nissinen, Social Psychologist and founding member of Seta

Listen to Jussi Nissinen’s account of how the words used when referring to sexual minorities have changed over time.

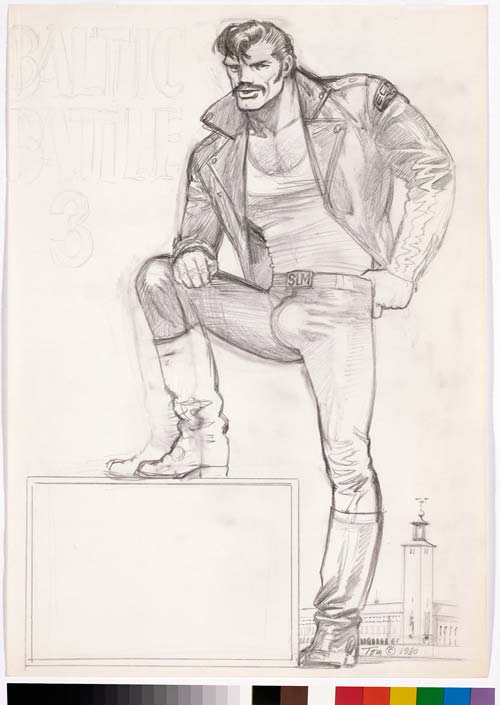

Touko Laaksonen’s Tom of Finland drawings contributed significantly to the renewal of homoerotic art. The drawings received mainstream attention in the 1990s. Laaksonen’s characters are strongly masculine and feature fetish elements such as leather, rubber, police uniforms and military uniforms. Tom of Finland has had great influence on how sexual minorities are depicted in popular culture.

Kuva: Touko Laaksonen,Tom of Finland, drawing 1980. National Gallery/Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art/Sakari Viika.

The character Kalle Laitela in the Finnish soap opera Salatut elämät is an example of a carefully elaborated homosexual fictitious character. Young people struggling with their sexuality can thereby identify with this character. American TV series about sexual minorities, including Queer as Folk and The L Word, began to be broadcast in Finland in the early 21st century.

Image: Fremantle.The character Kalle Laitela portrayed by actor Pete Lattu.