Equality for sexual and gender minorities was originally promoted mainly by associations and organisations including the Second Beam Group, the Psyke Discussion Forum and Seta, which were formed in the 1960s and 1970s. Gatherings, protests, education, articles and publications increased general awareness of sexual and gender minorities. Their increased visibility in public and in media influenced the atmosphere in which political decisions concerning sexual and gender minorities were made.

Listen to Jussi Nissinen’s presentation of Seta’s activism.

Legislative changes concerning sexual and gender minorities began to be debated in the 1960s. In 1966, Member of Parliament Jouni Apajalahti of the National Coalition Party proposed changing Chapter 20 of the Criminal Code to remove the prohibition of homosexual acts. Apajalahti argued that the ban prevented homosexuals from attaining equality with heterosexuals by upholding a judgmental attitude towards homosexuals and creating feelings of guilt among them. During the ensuing political debate, many other perspectives on the issue of decriminalisation emerged. Some members of parliament held the view that decriminalising homosexual acts did not mean condoning them, but rather making it easier for those suffering from the illness of homosexuality to seek help and treatment.

The prohibition of homosexual acts was removed from the Criminal Code in 1971. However, the decision on decriminalisation was accompanied by a ban on encouraging others to engage in homosexual acts, and the age of consent for homosexual acts was set at a higher age that that for heterosexual acts.

Ban on encouraging homosexual acts 1971–1999

The decriminalization of homosexual acts in 1971 was accompanied by a ban on encouraging homosexual acts in public.

The one who publicly encourages members of the same sex to engage in unchaste behaviour is to be sentenced, for encouraging unchaste behaviour among members of the same sex, to a penalty as described in subsection 1.

Criminal Code of Finland, chapter 17, section 9, subsection 2

The ban on encouraging homosexual acts influenced how the media dealt with topics concerning homosexuality. Although no one, as it later proved, would be penalised for violating the ban, its mere existence in the Criminal Code merited caution when discussing homosexuality. According to Jorma Hentilä, politician and former Chairman of Seta, the ban on encouraging homosexual actsgave publishers a convenient official reason not to produce programmes or texts about homosexuality, their true motivation for not doing so being that they did not want to promote the visibility of homosexuality in media.

Listen to Jorma Hentilä’s account of the legislative changes.

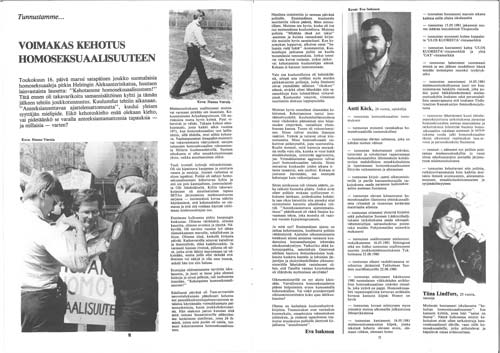

Protesters in front of the Parliament Building opposing the ban on encouraging homosexual acts. Big signs were used to display the statements of the protesters to the public.

Image: Seta Magazine 2/80.

Many considered the ban on encouraging homosexual acts inconsistent since it prohibited public encouragement of acts that were no longer illegal. The ban received criticism, the most publicised of which took place during Seta’s Liberation Day protests. Protesters carried signs encouraging homosexual acts, thereby openly challenging the ban on doing so. The police did not actively intervene against this kind of public provocations against the ban.

During the Liberation Day protests of 1981, the police confiscated protesters’ signs with words encouraging homosexual acts. In response, the protesters made a collective confession of guilt regarding their call to homosexuality. The prosecutor, however, concluded that the protesters had acted on a whim and would consequently not be prosecuted. Similarly, a petition calling for violations against the ban was signed by protesters on the Liberation Day of 1984 and submitted to the police. This resulted in no consequences for the protesters, who next posted the petition in the window of Seta’s headquarters to enable passers-by to read it.

Listen to Jorma Hentilä’s account of the significance of the Liberation Day protests.

Age of consent 1971–1999

When the Criminal Code was changed in regard to homosexuality in 1971, the age of consent for heterosexual acts was set at 16 years and that for homosexual acts at 18. The law was thereby still discriminatory in regardto sexual orientation.

The age of consent is the lowest age at which a person may choose to engage in sexual activities. Sexual relations with a person below this age are thus illegal.

According to the so-called seduction theory, which prevailed for a long time, young boys in particular matured late and were very impressionable. This being the case, homosexuality could “infest” these boys if they were sexually harassed by adults. The decision to set the age of consent higher for homosexual acts than for heterosexual ones may have been motivated by the prospect of harassed adolescents turning into homosexuals, more so than by a concern about the harassment as such.

Higher age of consent for homosexual acts and the ban on encouraging such actswere present in the Criminal Code until 1999, when the age of consent was set at 16 years for all sexual acts regardless of sexual orientation. During the preceding debates on how the law should be changed, some promoted lowering the age of consent to 15 years. According to unofficial sources, legislators did not wish to lower it below 16 years since they wanted to protect boys, who were considered to mature later mentally.

Listen to Jussi Nissinen’s account of the age of consent.

The effects of legislative changes

Although homosexual acts were no longer illegal, higher age of consent for homosexuals and the ban on encouraging homosexual acts meant that homosexuals had not attained equality with heterosexuals. The public atmosphere and unfavourable attitudes held by many, including police officers, contributed to a feeling on inequality. This led to many crimes against homosexuals not being reported to the police. Reasons for not reporting crimes included the fear of becoming a victim, being revealed as a homosexual or not being taken seriously by the police.

Listen to a contemporary’s account of covering up homosexuality.

The debate on changing the law was in itself traumatising for many. The opinions and arguments that surfaced in the parliamentary debates were often emotionally charged and denigrating. Social psychologist Jussi Nissinen commented how ”grown-ups in parliament, ostensibly representing the people, spoke in a repulsive and belittling manner. Many remarks constituted outright hate speech and could open painful wounds among the minorities.”

Listen to Jussi Nissinen’s account of the significance of parliamentary debates.

The depathologisation of homosexuality and its removal from the list of diagnoses in 1981 was, in contrast, not a parliamentary decision but concluded behind closed doors by the National Board of Health. Prior to this, however, Seta had written several letters urging the National Board of Health to depathologise homosexuality. Newspapers rarely discussed the issue of depathologisation as a topic in its own right, but rather as part of the wider debate on the rights of sexual minorities. Jussi Nissinen described the feeling of hearing the decision on depathologisation as a wonderful springtime.

The decriminalisation of homosexuality enabled individuals to publicly declare their homosexuality, and this contributed to making the public perception of homosexual life more positive. Such public declarations by members of the intelligentsia and famous artists were particularly effective in increasing public understanding and acceptance of homosexuality. Persons who were held in high regard were more difficult to criticise, being elevated above scorn and ridicule. Public declarations of homosexuality had a significant impact, demonstrating that homosexual life was not always pitiful and deplorable.

Listen to a contemporary’s account of public declarations of homosexuality.

Programme of Seta’s Liberation Day of 1986. The topic of that year was “The right to one’s own life”.

Click the image to read the article (in Finnish only).